That morning I ordered waffles, which I almost never do. Funny I can recall the waffles with such clarity (syrup-soaked, dense) and next the walk home along a Chicago street bordered by pudgy brownstones. It was a sunlit April day, the bitterness of Midwest winter finally releasing its grasp. My phone rang — “book the next flight, come home” — and what happened after I only know as disconnected flashes in my mind.

A plane’s wing tip sears through ink-black sky; a flight attendant asks, “Are you OK?” The question, unanswered, lingers in stale cabin air longer than it should. A car ride to O’Hare, there wasn’t enough gas. A gas station, a voicemail.

“Melis, it’s Mom. I found the right paint for your bedroom wall. Either the butter yellow or the lemon yellow. Probably the butter, possibly the lemon. I’ll send samples soon …”

And a girl, 20-something and sleepless, sits atop the radiator of an empty hospital hallway, staring at taupe walls and colorless tiles patterned on the floor. Maybe a nurse comes by, places a hand on her back. Maybe she’s alone.

These details have since been weeded over by the forgetful tendrils of time.

But to me it doesn’t matter. They’re not the stuff of my mom’s legacy anyway. The finale was too cold, clinical, outlined in thin breathing tubes and cadenced with the discordantly bright chirps of medical artillery. Legacy, at least as I see it, implies a great story and you can’t tell any great story by starting at its end. So here’s mine from the beginning or better yet, here’s hers.

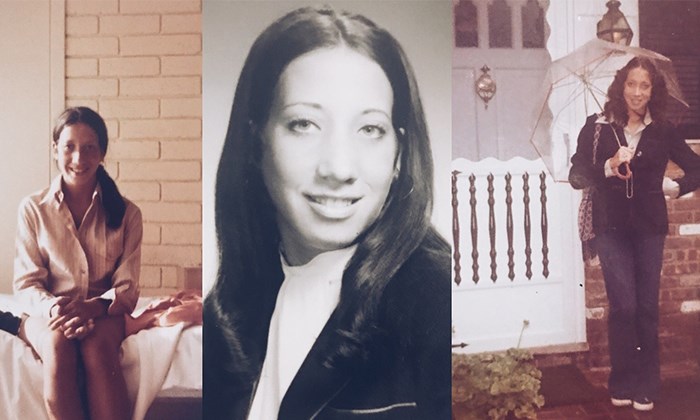

To understand my mom, you’d probably have to meet her. She came from a large, tight-knit family, was somewhat tall, forever skinny, with intensely blue eyes and a head of wild curls she could never quite tame. Her demeanor was an amalgam of honeyed optimism, humor and the kind of chronic selflessness you only find in the movies. It pained her to say anything bad about anyone, ever. When a turkey sandwich was placed in front of her at our local diner, she thanked the waitress and meant it.

Growing up in a 1960s world where cystic fibrosis wasn’t recognized like the disease is today, nobody suspected anything was amiss. As a young girl her fingernails were oddly spoon-shaped, she’d cough here or there but my mom’s early years were marked by relative normalcy.

It was age 18 at Miami University when she got sick, really sick, and doctors pegged her with tuberculosis, prescribing the full cocktail of necessary medications. Only a sweat test administered weeks later by a pulmonary specialist revealed the misdiagnosis; she had CF.

Nothing in the news put her life on hold. She recovered from the bout, graduated college, went to Woodstock wearing a leather-fringed vest and pitched a tent there in the rain.

In her 20s, she worked for my grandfather as bar manager at one of the liquor concessions our family owned in the Broadway theaters splashed across Midtown Manhattan. She met my dad, they fell in love, married, played tennis, traveled. Life was sweet then, a sing-song chorus in the key of Major C. Still a feeling persisted this was just the intermission, something far grander could be found in Act 2.

“I was wrong, Melis. The butter yellow won’t work, the wall’s too big for such a bright color. By the way, I know you have a date tonight so I won’t call again, I’ll text. Call me later if you want, I’ll wait.”

The other thing you have to realize is that motherhood had been the pièce de résistance of my mom’s existence. The first eight years of marriage were spent seeking it, ignoring bleakly delivered admonitions of medical practitioners who shook their heads, “No.”

Undeterred but frustrated after almost a decade of trying, she turned to her brother — my uncle — a doctor working at the time for a holistic center in Long Island, NY. He told her about a Chinese woman knowledgeable in ancient herbal remedies and acupuncture, and days later found my mom at the behest of the slight, soft-spoken physician. It would be irresponsible to say this woman did it but for whatever reason, six weeks after my mom started the regimen, she was basking in prenatal bliss.

Pregnancy proved far from easy and she spent the final two months in the hospital short of breath and pneumonia-ridden. My mom would later tell me how she became good friends with the nurses on the floor, (oh my gosh Mom, of course you did) and allegedly, when I was born they all came out from their rooms, stethoscopes waving, and clapped.

It made sense I should grow up a child of the stage; from that very first breath applause heralded me as my mom’s finest work of art. Performance — specifically, singing — defined my entire adolescence and beyond.

There’s a scene in my mind, an audition for The Lion King, on the third floor of a rickety Lower West Side walk-up that smelled of mildew and dancer’s sweat. My mom paused, shaky hand on the rail, and ascended the meandering staircase one slow, huff-breathed step at a time. I never made the connection this was a requiem to an ever-debilitating disease; it was truth plainly told and not a warning of what would come.

“Hey, me again. I thought about something else for your date. Make sure you give him a big kiss when you see him. And not one of those quick ones, Melis, a real kiss. Then after, say that was from your mom.”

People ask, “Did you know?”

Well, did I know what? That my mom wasn’t like other moms? No, I had no idea. She was more involved in every corner of my life than anyone could be. I was an extension of her very being, a long-awaited gift celebrated with interminable attention upon receipt.

Maybe the lack of awareness on my part was because cystic fibrosis had been more a religion for her than a dilemma, and one whose tenets of treatment were followed with exquisite compliance. She did three, one-hour breathing inhalations a day with the discipline of a disciple, packed a suitcase full of nebulizers that trailed us on every vacation, completed at-home IVs when she’d develop a bad infection. I’d sit in bed with her and watch TV while the medicine went to work. Her left arm was sore from the needle so I didn’t touch it. Such was life, the way I always knew.

When she developed diabetes in her 50s that became yet another truism of devout stature. She’d check her sugar before every turkey sandwich, and if we were driving somewhere and she’d start to sweat from low blood sugar, I’d make her pull over to relinquish the wheel to me.

“Melis, it’s Mom. I can’t get any sleep here, thought you might be up …”

A clock read after midnight (maybe). Most friends and family had gone home until morning but I couldn’t leave the small room, surrounded in the half dark by machines that hummed a battle song well beyond defense. Time staggered back and forth then twisted sideways, at last retreating like a senseless coward until there was no time left.

If you want big-picture legacy, here’s the final refrain: My mom wasn’t someone who lived for 60 years with cystic fibrosis. She was just someone who lived.

“Melis, it’s me. How’s the studying? The nurses want to see you again. They asked about you tonight so I showed them the article you wrote on watermelon. It feels like I’m not getting any better … What if I don’t get better? I know you’d say I’m crazy, I’ll get better. I’m trying. And you’re right about the paint, the lemon yellow works. Oh, I have to go. Talk later, OK? I’ll call you tomorrow.”

This post somehow showed up on my desk and it was so amazing. So well written.

Can I get your email and drop you a private message.

thanks4thefish42@gmail.com

Love the email address!!

How painful.. how touching..

Discover from WordPress sent this post to my inbox. Your words are poignant and reading this I feel like I got a chance to know your mother. Thank you for writing and sharing it – I’m going to go call my mom now.

She sounds like both a brave and admirable woman.

Beautiful testament!

I imagine she never really met a stranger. What a beautiful tribute. This inspires me as I’m trying to sort the legacy of my own mother. Thank you for sharing.

A beautiful tribute to your mom and your relationship with her, artfully written. Thank you.

This is such a poignant testimony to you mother and not only the fight she put up and the zest for life but her love for you. Beautifully written. Thank you for sharing. <3

I cried, then smiled, then giggled then cried again. This was so full of emotions. So very raw and real and so very well written. Your my fav on my reading list. Hugs!

Reblogged this on pressagrun.

Great post – both encouraging to just live and live your life. But also appreciate just what a great writer you are in general

Reblogged this on Joie. as your friend.

“I swear I lived” -one republic..

Thanks for sharing!

Boa noite

I appreciate your writing. Yet, I appreciate the love you have for mother a tad more.

Amazing, makes me recognize the gift of my ever present mama

☺️💙

This is beautifully written, I’m lost for words.

This is absolutely beautiful. Your were words were breathtaking!

Absolutely perfect! You’ve captured so much that resonates with me! Truly beautiful writing

Nice post

What a touching story

Beautiful tribute to your mother and your relationship! Thank you for sharing.

I grew up with a Mom in and out of the hospitals. I no longer have her, but now that I am older realize she was one of the strongest people I’ll ever know and blessed to have as a mom.

I saw a quote once, “God gives us the children who need us.” So true.

Loved your words.

Thank you for sharing. This was so beautifully written ❤️

This really moved me. I can vividly imagine what you have gone through with your mom. She really is a strong woman.

I lost my sister to CF when she was just 19, she was a beautiful fearless soul who worked tirelessly and selflessly for others, in her journals she referred to her body as her battlefield over which the white flag would never fly but that one day the white knight would come to save her and save her he did. I myself am struggling with infertility and you’re words on you’re mothers behalf hit my heart like a bell longing to be rung, I am still waiting to meet the soul, the extension of my being, a long awaited gift to celebrate, I pray my child has a mind and heart like yours, this stranger who speaks to the heartbeat of other strangers. Truly beautiful encountering your heart in mourning and celebration today. Thank you.

This was a beautiful well written post. God Bless your mother soul she is definitely a strong, loving woman.

So deep

How fortunate you were to have each other. While I’m not sure how you came to be in my inbox, it seems a bit of a reminder to get in contact with my old WP friend, Carly Jay Metcalf. You can find her excellent blog on WP or her TedX talk on youtube. She is the most courageous warrior, CF survivor, ever. Thanks for sharing your lovely tribute to your mom.

This is really touching.

You’re an awesome writer.. you touched my heart and now, I’m starting to miss my mom..

makes me want to talk to my mother more

This is so beautifully written. The love is almost palpable! Such a wonderful tribute to your mum. Thank you so much for sharing.

you are a good daughter

Admirable woman and an example to all of us! Thank you for sharing you mom so beautifully with us.

Reblogged this on being.ellieee and commented:

Im touched😭😭❤

Really powerful well written post really enjoyed it 🙂

https://amumwithsocialanxiety.wordpress.com/2017/11/16/what-its-like-being-a-parent/

I can understand how your emotions are. In my case, it was my grandparents. Being a big family, we lived together. My grandparents were just like my parents, sometimes even more. Sadly, my grandfather suffered from Alzheimer’s and my grandmother from Liver Cirrhosis. It was tough. I miss them everyday. Your post was beautiful. Excellent writing. I am definitely following your blog. I am looking forward to more. Good job!

Beautiful

Beautiful. Came here by chance. Thank you for sharing this.

This profoundly pulls at my heart strings. Love the way her identity surpasses each and every circumstance and continues to shine through. Sending love and light. 💕✨

Really

Reblogged this on Planktonenteen Writer.

Beautifully written 💛

Beautifully written. Thank you for sharing her with us.

Hey!

Its strange story. The recollections are very touching. Many words couldnt be fitted in my understanding. Perhaps I couldnt apprehend there connection. Puzzled. I would like to read more thanks.

Great!

An awe-inspiring work! 👏👏👏📖🕯🍀💖

Very Inspiring

This piece is amazing..

Wonderful post

This is very beautiful! Thank you for sharing this ❤

That is the most beautiful post I have ever read. Thank you for sharing her world with us.

Your words reached deep in my heart. Thank you.

I truly loved your blog..

Amazing posts..❤

You have truly inspired me dearest to be a great blogger💙

Reblogged this on Shards of Bards.

That’s wonderful…

Loving tribute to your Mother. What an inspiring woman!

Very touching. Very nice! More a story of an inspiring life than a death. As someone whose Mom died at 59 (the age I happen to be now) I am particularly uplifted. Thanks.

She is beautiful. Strong.

Very inspirational ❣️❣️

Beautifully written piece💕

Your words went right to my heart. Beautiful.

Beautiful!

a loving tribute to your mum. Inspiring work that left me really connecting with not only the piece but with you and the resilience of your mum

Nice

Beautiful story. “She was just someone who lived” So true.

Beautifully written:)

I could relate to your mom’s CF challenge. i have it myself. Quite a disease. thanks for the story.

This is such a beautiful piece. There is so much love here.

What a stunning article. Beautifully captured ❤️

Absolutely amazing and well written.

It’s amazing when this beautiful person mom inspires us. It made me cry. Really really really well written. One of the finest pieces. Keep going 🙂

very touching post

This is a beautifully written piece. Your mother was so strong and I’m so glad you’re able to remember her the way you do!

This was full of emotions…Thanks for sharing ☺️

I am sharing this with my family member with CF, almost 30 and going strong. Blessings to you.

This is a beautiful, beautiful honor to your mom.

This was beautiful. Thank you for sharing.

Touching post. Really puts life in perspective. Shows me not to take people who care about me for granted. Thank you.

Wow..fabulous……My eyes filled with tears😭❤️

Great job👍🏻

I lost my mom when I was 13. She died from breast cancer — but I knew her more as mom. Your story is breathtakingly beautiful. Thank you.

Beautiful post and tribute to your mam. She sounds like a remarkable woman.

Amazing and very touching… May her beautiful soul live on in you.

“Wow” is all I can say.

Well described with so much love so sweet

I really like your post the love you enmeshed within it’s out of the world 😍

Very beautiful and so touching.

So wonderfully and powerfully written – not over sentimental – just right. I am sad for your loss but happy that you had such warm relationship with your mum.

Reblogged this on Magic of the Phoenix and commented:

I think this story could be used for any mother. Whether it was a mom with a disease/illness or a mom that completely healthy, you never know what that person has gone through to become the mother you have or become the person you think you know. That’s a beautiful thing about having a mother and daughter relationship. Not everyone has those. So hold tight to yours.

a tear rolls down my eye. I cannot remove her name from my contact list. Thank you for bringing her back to life.

a tear flows down my cheek. I cannot take her out of my contact list. She is truely missed.

I feel as if I know your sweet mama after reading this. My heart is with you and I hope that deep peace floods your every thought. Blessings.

Wow! This is so beautiful.. It was heart touching and moving!!

Please read a poem that I have written as a tribute to all our mothers.

https://theunspokeninus.wordpress.com/2017/12/16/mother-a-blessing/

So amazingly written! It brought tears to my eyes.

So touching. My heart goes out to you.

So very touching

Very sad but I love the way you describe her with so much life <3

Really nice!