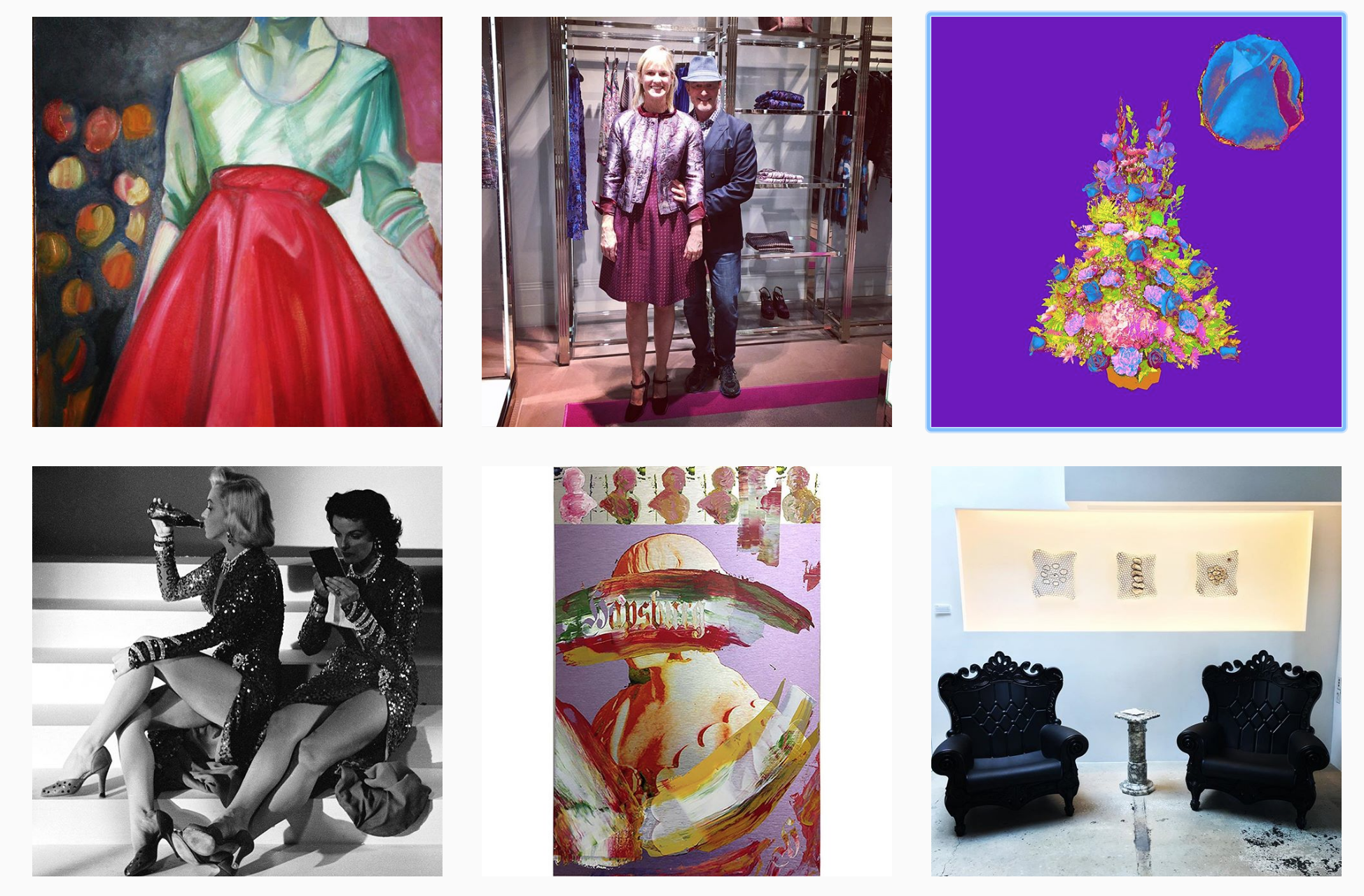

[Cover image via Instagram.com/redcarpetluke]

In which I talk to brilliant costume designer/fine artist Luke Reichle and in re-reading his answers to my questions while creating this post, sense his creative, electric energy with such fervent palpability, it practically buzzes off my computer screen and makes me feel all sorts of inspired …

MELISSA: When not crafting fine art, you’re a style guru and successful costume designer. How did you get your start in the entertainment business?

LUKE REICHLE: I hit New York right out of fashion school and spent ten years in the design rooms of Calvin Klein, Perry Ellis and Alexander Julian. Ultimately I moved to Europe as creative director of the ill-fated Bjorn Borg Design Group, the story of which really has to be told in person as it requires hand gestures.

Runway # 6, oil on canvas, 1986 by Luke Reichle

Joel Grey, The Fantastics! 1995

It’s obvious you have an abundance of creativity just oozing right through you. What is it about fashion and style that appeals to your creative sensibilities?

My interest in fashion grew out of my studio practice. For me, fashion has always been another art medium. It incorporates principles of painting and sculpture. And then there’s the unknown element of what happens to it when it goes on a body. For film work, it’s even more complicated, a matter of working in two dimensions (the sketch) into three dimensions (the costume on an actor) and back to two dimensions (the image on a screen.) A fabulous challenge.

From ABC’s hit show Castle to Without a Trace and CSI Miami, you’ve outfitted stars from some of today’s most popular high-drama, high-intensity TV series. In what ways do you tell a character’s story through his/her style?

It all starts with the script. I work in the service of the story. It’s not as much about actors looking good – although that is often the result – but rather looking right for the part. If I stick to the story, the look will follow and be an authentic representation of the character.

Scoundrels, 2010

Let’s talk for a minute about villains versus heroes. Is there any way you reflect a character’s inner goodness (or lack thereof) through his/her sartorial choices?

Although I use visual cues to communicate the nature of a character or scene, you don’t want to ring that bell too loudly or it will come off as false, not organic to the portrayal. Filmmaking is a collaborative art. You have other people’s ideas of the characters that come into play. The director, writer, producer and certainly the actors, come to the project with various interpretations. It’s up to me to balance that with my vision as well as the physical logistics of the production, like, what color is the couch they’re going to be sitting on. Audiences are increasingly sophisticated, so you have to go beyond the idea of White Hat/Black Hat. Whether hero or villain, I prefer to design against type and build a narrative within the costume that implies more complex depths, a method that gives the actor a lot more to hang the character on.

Tony Goldwyn, Without a Trace, 2006

Transitioning to fine art, you have three current projects — “The Fitting Room,” “Titans” and “The Hairdo Project.” I want to start by asking about “The Fitting Room,” a series of digital portraits that explore the intersection of image, character and expression. As Meryl Streep once famously described it, a costume fitting is a meeting of the designer, the actor and a “third person,” who the actor must subsume his or her own personality into in order to become the character being portrayed. Is there a particular memory you have that you drawn on for this collection … Maybe a time when you were in a fitting with an actor and he or she was completely changed, as if by magic, by the costume you selected?

All the images in The Fitting Room are taken from costume fittings over the past twenty-five years. The portraits seek to represent the point in the fitting where “the third person” appears. This happens at different points for different actors. For Albert Brooks in The Scout, it was when he put on four pound wing-tip shoes I found for him. For some it’s the corset, for others, the entire look. The thing all these moments have in common is the emergence of a sense of essential rightness, the moment when the character begins to speak to the actor through the clothes.

Brokeback Boyfriend (Colin Farrell) 2015, archival inkjet print on etched aluminum with hand embellishment by Luke Reichle

You began “Titans” as a meditation on the elemental nature of color and it quickly morphed into a commentary on the culture of image and how our quest for physical perfection can be both an act divinely inspired or one that brings out the most monstrous qualities of the human character. It’s interesting to think about how our physical hunt for beauty manifests itself in such internal and emotional ways. How do you portray this inner struggle for god-like exterior beauty in your art?

A great deal of my work springs from the struggle involved with self-image. It used to be that women were the ones pressured to look a certain way. Now that the ten-pack is the new six-pack, and muscled torsos are used to sell everything from dental care to cars, men have increasingly joined the ranks of the image insecure. Titans is a commentary on gym culture and how desire leads to distortion. For me, the most heartbreaking of these images is The Minotaur in his Youth. It isn’t his fault his mother had sex with a bull but he is left with the consequences. He’s imprisoned in a maze of mirrors and expected to navigate with an ever-changing set of rules, a landscape familiar to girls and women for millennia.

The Minotaur in his Youth, 2016, archival inkjet print on etched aluminum by Luke Reichle

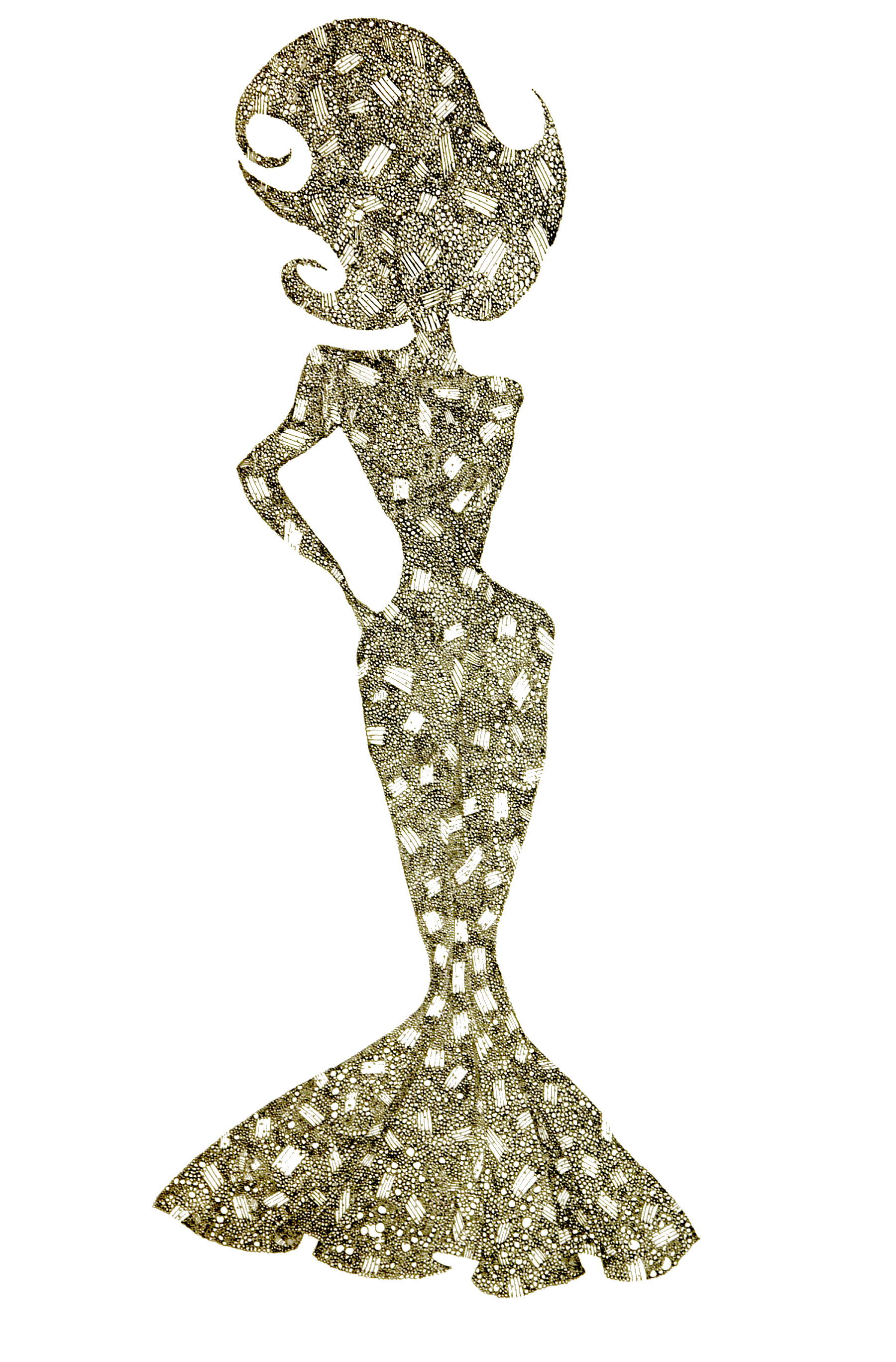

“The Hairdo Project” is heavily influenced by Hanna-Barbera villains, girl groups of the 1960s and back-page wig ads from your sister’s True Romance magazines, with their hair-dos as the ultimate expression of pre-feminist artifice. How did the idea for this project come about?

Around eight years of age, I began drawing figures in the margins of my schoolwork. What they all had in common was big hair, a curvy body and LOTS of cleavage. This, it turned out, was very distressing to the nuns. I was punished but wouldn’t stop. The figures turned up everywhere. Eventually a campaign of humiliation in front of my classmates, (“You want to be a girl? Is that it? You’re drawing girls because you want to be a girl?!) drove these figures underground. They didn’t re-emerge until much later, showing up in painting and costume renderings. The Hairdo Project is an outgrowth of this figure, and my obsession with hairdos and hairdressing that emerged at about the same time. I was fascinated by the ads for wigs in the back of women’s pulp magazines like True Romance—where every article title provided a thought balloon for a Roy Lichtenstein painting. My Love Led My Man into a Terrible Trap! You get the idea.

Supreme Being, 2015, pigment ink on Arches paper by Luke Reichle

Glamour is a state of mind, you say. Explain …

It’s not about the dress, but she who inhabits the dress. The root of the word, “glamour” or “glammer” refers to a spell that is cast to make someone appear larger than life. “To put on a glamour,” is exactly what we do for film when we put an actor, “through the works,” in hair, makeup and wardrobe to create an image. If you don’t have an innate sense of glamour, it can be instilled in you. I’ve seen it too many times, where a client or actor comes out of the process transformed, having recognized in themselves an expanded concept of who they are. It was always there. Having a sense of your own glamour can be the difference between you wearing the dress and the dress wearing you.

Castle, 2010

Let’s return to the concept of fashion storytelling. Which designers today are crafting compelling narratives through their clothes and how do they do it?

You could say that the most successful narratives are being drawn by those that adhere most tightly to their brand. MaxMara, Giorgio Armani and certainly Ralph Lauren are top examples of this. Etro does it with color and pattern, Stella McCartney with rock and roll chic, The Row with edgy luxury. Prada and Rodarte compete for most artsy/quirky, while houses like Botega Venetta, Balenciaga and Valentino mine their extensive archives to bring us updated examples of their greatest hits.

Finally, fill in the blank: As I define it, “Art is _______ …

… pointless without passion and a purpose.”

Thanks for the insightful interview Melissa! In the headline photo, the image on the lower right is a pic I took while visiting Weinberger Fine Art, one of a group of very advanced galleries in Kansas City. The three pieces on the wall are by Brett Reif, a brilliant sculptor. Kim Weinberger has an awesome program going on in her gallery, situated in the very happening Crossroads Arts District. Check them out at http://weinbergerfineart.com

Thanks for the additional info! I added a photo credit to your Instagram page at the top of the post 🙂

I’m glad to hear I’m brilliant…totally agree! Ha! Great interview. B Reif