“The most useful of the natural sciences, yet the least advanced, strikes me as being the science of man.” – Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Emilie Valentin watched the early morning light, filmy and thin, escape from her drawing room window as she took a third and final drag on her half-finished cigarette. She wasn’t a smoker – no woman was – but she always took kindly to those très gauche activities forbidden for the female and also, quite frankly, to anything looked upon as decidedly lower class. Emilie was both a fully curved woman and well enough off to afford fine gowns or the installation of marble floors below her bathtub but this penchant to smoke represented a revolutionary defiance, which gave the secret of cigarettes its most enticing appeal.

Emilie’s husband, Jacques-Henri Bernadin de Saint-Pierre, was the only person in France who knew about her smoking. Of course she had to tell Jacques-Henri, her sensitive, handsome crusader of small animals and plants whose hand she took in marriage on a soft, sandy beach near Cannes four years ago. How could she not reveal her secret to such a gentle man, known for walking the manicured gardens of Paris on late afternoons with that bulbous-nosed thinker, Rousseau, quoting lines written by Voltaire and lamenting on la tragédie de manger de la viande? Of course he must know.

“If it makes you happy, my darling Emilie, it makes me happy in every way,” Jacques-Henri would say, his pink lips curving to a smile, when she asked if he minded la fumée. “I’m a valiant supporter of your cause, toujours.” Then he would grab her by the big, silly ruffles of her dress and she’d laugh into the blonde curls of his hair and his brilliant mouth would settle on hers. Oh, la beauté de l’amour; how sweet life could be!

And sweeter still each day, even as things so dark as death and war and La Révolution drummed its guillotined, bloody beat outside her drawing room window. She’d never sing this song but heard it all the same.

Today, she was meeting Jacques-Henri at noon for a surprise spéciale as he had called it last Monday with that wicked but enlightening late-night grin reserved only for his chère Emilie.

Twelve o’clock found Emilie standing beneath the shiny September sun and a blue smear of sky, which hovered with noiseless, bright-white clouds above a metal set of gates. This was the entrance to Jardin des Plantes, the royal herb garden Jacques-Henri often visited to study and conduct his research. And there beside the cool, steely entrance was her husband, on time as always, outstretched hand already warm when she twined its fingers between her own.

“Oh my dear, I love this place!” Emilie squealed and Jacques-Henri nodded, leading her across a green stretch of short, perfectly cut grass, bordered by the serenity of leafy trees Emilie could nap under for days.

“After today, I think you’ll love it even more.”

Emilie really did enjoy her infrequent trips to Jardin des Plantes, and not just because the tea served among the gardens tasted of fresh air and ambrosia or because the beauty of flowers somehow made the brassy, unfair world beyond seem easier to take. She enjoyed it just as she enjoyed a good smoke, delighting in the Jardin’s emerald tinges of the unknown that seemed as appealing to her as the flickering, orange embers atop a woman’s cigarette.

When they reached the edge of the grass, Emilie released Jacques-Henri’s hand. They stood before a cage, big and clean, made from the same bars framing the boundaries of the garden.

“What is it?” Emilie asked.

“Look,” her husband said.

She saw, or her eyes told her she saw, a tiger. Not a painting of a tiger like the one inside her chambre or a thought about a tiger made up in her mind. But in this cage she saw a real, breathing tiger laying beside a real, breathing lion, and Emilie almost fainted on the spot.

“Jacques-Henri! What is this? Why are they here?”

Jacques-Henri said this like he said what kind of marmalade he wanted on his toast or how the weather would appear that day, matter-of-factly and with the absolute conviction of a man tasked with caring for all the lions and tigers of France.

Emilie should have been excited, this she knew, to see a real, breathing lion and tiger not more than three feet away. She had never seen either animal before, (at least not in this living, breath state) and should have thanked Jacques-Henri for revealing to her his own hidden secret. Instead, every inch of her body wouldn’t allow her mouth to speak.

The majestic tiger and kingly lion both appeared as beautiful beasts, shiny coats and gleaming teeth, at war with their sad, big eyes. Were these animals aware of the burden they now carried to adopt some new brand of freedom, one which called for the right to live inside a cage? C’est faux, thought Emilie. This is wrong.

“So? What do you think?” Jacques-Henri seemed impatient, his chin twitching.

“I thought you wanted to save animals,” Emilie replied. “Why keep them here when a life inside is so dull and … grise?”

Jacques-Henri laughed but Emilie didn’t care for the sound. “Rousseau tells me, ‘Do no injury to your fellow-creatures,’ and he means it to extend our rights and morals to both animals and man. That’s what this menagerie will do, Emilie, it will save these living beings from certain death and help us come to understand them and their exotic ways.”

“Perhaps,” Emilie answered, lips pursed.

“Ah. You’re not convinced, ma cherie.”

In the silence that stretched between this string of words and the next, Emilie made a decision, quick and true. She would be the devoted wife who made a promise on the French Riviera four years earlier to honor and obey this man whose heart she shared as one, toujours. So the reply that followed was the only one she could give.

“If this makes you happy, my darling Jacques-Henri, it makes me happy in every way.”

She left the Ménagerie du Jardin des plantes, running home and returning to the comfort of her master bath with the oversized tub. Emilie ripped off her dress with due dramatic flair and removed her tight, steel-caged corset, forever holding her inside the boundaries of its boning and cloth. From somewhere on her marble floor, she shed a single tear, crying for La Révolution, for all its lions and tigers now caged, for all its women with smoking secrets kept in sunny drawing rooms and for all its men thinking they had the right to kill. She lit her cigarette, watching the coils of smoke leave her mouth and float easily toward the window, then thought about what a grand day it was to have the courage to set them free.

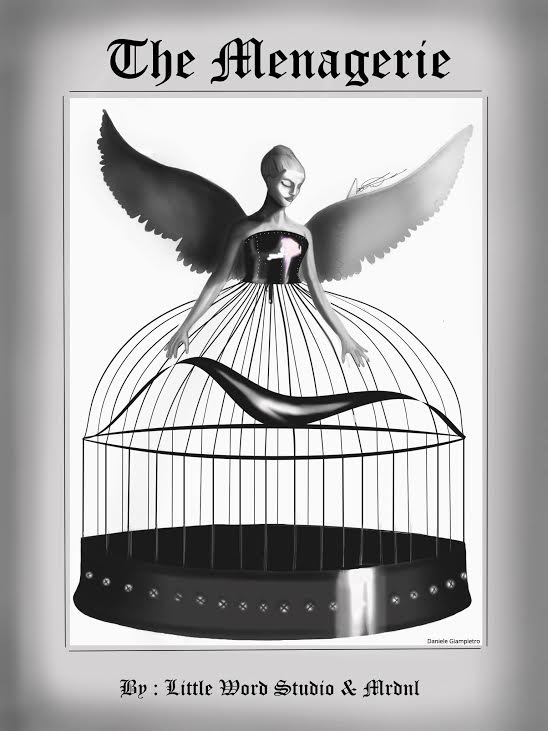

[This story is part of the little word art series, creative collaborations with talented and passionate artists from around the world. This drawing of Emilie Valentin was drawn by Daniele Giampietro, an Italian fashion designer and illustrator. To view more of his amazing work, visit Daniele’s Instagram account here.]

This day, you set your writing free with matching imaginative art. Thanks for the Instagram link too.